Why Demographics Are Failing Your Personalization Strategy (And What Actually Works)

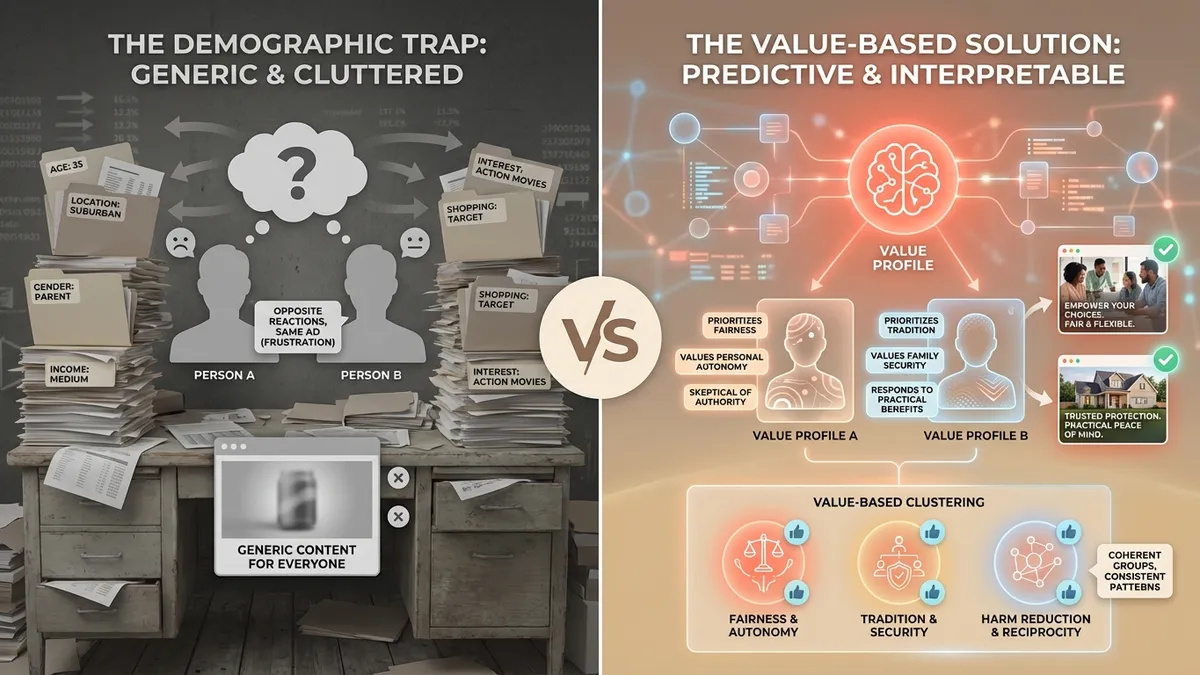

At Navay, we’ve spent the past year building human simulation systems. In conversations with marketers, one pattern keeps coming up: they obsessively collect demographic data, build elaborate segments, then wonder why their “personalized” content feels generic to everyone. Two 35-year-old suburban parents can have opposite reactions to the same ad—a frustration marketers describe constantly, and one that demographics can’t explain.

A new paper from researchers at Google DeepMind, Stanford, and Heriot-Watt University finally puts numbers to what we suspected. The short version: demographics are a noisy proxy for what actually drives decisions. The real signal lives in something more fundamental—people’s underlying values.

The TL;DR

The Bottom Line: Researchers developed “value profiles”—natural language descriptions of a person’s underlying values extracted from their behavior—that preserve 71.1% of the predictive power of full behavioral demonstrations while being dramatically more interpretable. When they clustered people by value profiles instead of demographics, they could explain individual rating differences far better than traditional demographic segmentation.

If you only take one thing away: Value profiles—compressed representations of what people actually care about—predict individual preferences better than demographics and offer a scrutinizable, interpretable way to represent human variation in AI systems.

What Are Value Profiles?

A value profile is a natural language description of what a person fundamentally cares about, inferred from their observed behavior. Rather than describing someone by demographic attributes (age, location, income) or surface-level preferences (likes action movies, shops at Target), a value profile captures their underlying orientation toward concepts like fairness, harm, tradition, and personal freedom.

For example, instead of “35-year-old suburban parent,” a value profile might read: “Prioritizes family security and tradition, but also values personal autonomy. Skeptical of appeals to authority, responds to practical benefits over emotional messaging. Strong orientation toward fairness and reciprocity in relationships.”

Demographics tell you surface attributes. Value profiles describe the underlying orientations that actually drive decisions.

Demographics tell you surface attributes. Value profiles describe the underlying orientations that actually drive decisions.

The key insight is that these value orientations are more stable than surface preferences and more predictive of reactions to new content. Two people with identical demographics can have completely opposite value profiles—which explains why demographic segmentation so often fails to predict individual responses.

The Research

Paper: “Value Profiles for Encoding Human Variation” by Taylor Sorensen, Pushkar Mishra, Roma Patel, Michael Henry Tessler, Michiel Bakker, Georgina Evans, Iason Gabriel, Noah Goodman, and Verena Rieser. EMNLP 2025. arXiv:2503.15484

What They Tested: Can we create interpretable, compressed representations of individual humans that predict their preferences better than demographics? And critically—can AI systems use these representations to simulate diverse human perspectives?

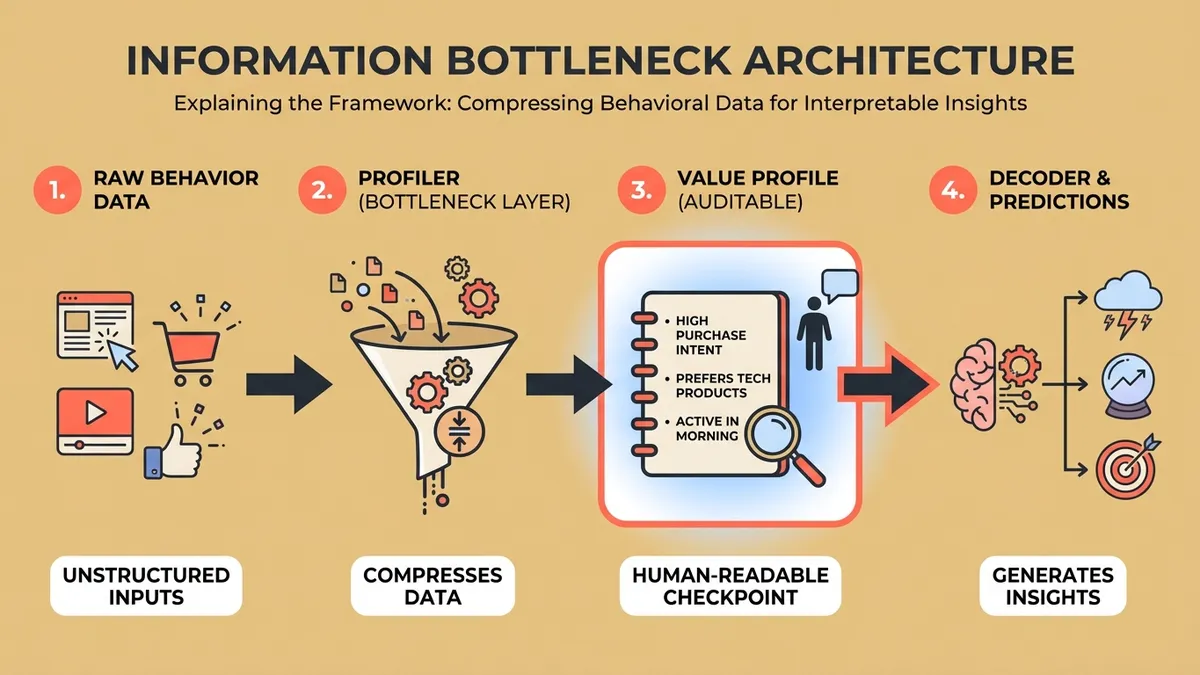

How They Tested It: The researchers built a two-stage system. First, a “profiler” model analyzes examples of an individual’s past ratings and generates a natural language value profile—a paragraph describing what that person seems to care about. Then, a “decoder” model uses that profile to predict how the individual would rate new content. They tested this on two datasets: one with 538 annotators rating potentially toxic content, and another with over 10,000 raters from the World Values Survey evaluating social and political statements. The key innovation is treating the value profile as an information bottleneck—forcing the system to compress behavioral signals into interpretable language that humans can actually read and verify.

Finding 1: The Information Hierarchy That Should Change How You Think About User Data

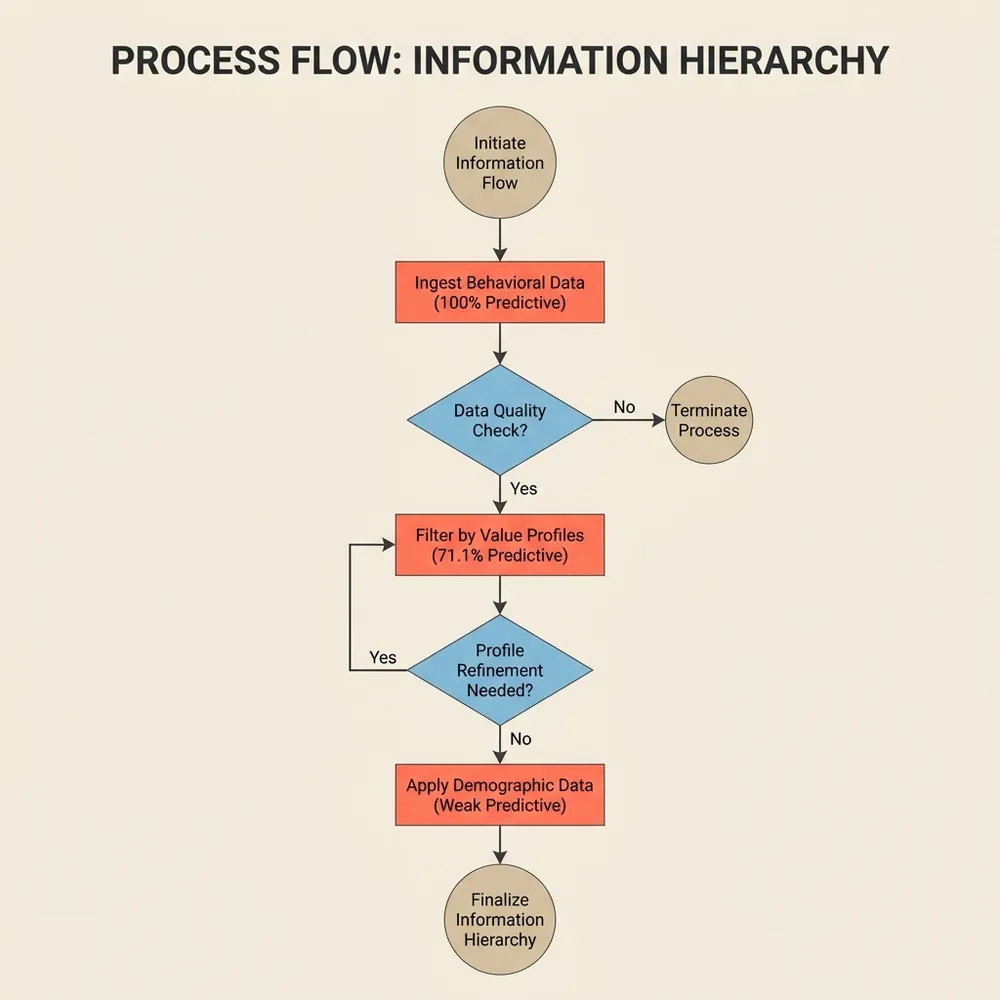

This finding from the research was unexpected: the researchers systematically tested what types of information best predict individual preferences, and the results establish a clear hierarchy that inverts conventional marketing wisdom. Behavioral demonstrations (seeing how someone actually rated similar content) contain the most predictive information. Value profiles come second, preserving the majority of that signal. Demographics trail in a distant third.

The information hierarchy: value profiles retain 71.1% of predictive power while remaining human-readable.

The information hierarchy: value profiles retain 71.1% of predictive power while remaining human-readable.

The numbers make this stark: value profiles compress extensive behavioral data into a single interpretable paragraph while retaining 71.1% of the useful predictive information on the toxicity dataset (measured as the percentage of behavioral signal retained). That’s not a marginal improvement—it’s a fundamental shift in how we can represent human variation. Adding demographic information on top of value profiles provided minimal additional predictive power, suggesting that demographics largely serve as noisy proxies for the underlying values that actually drive decisions.

This inverts the conventional wisdom that “more data is better.” You don’t need a hundred data points about someone’s age, location, and purchase history. You need a clear understanding of what they actually value—and that can be compressed into readable English.

Finding 2: Value-Based Clustering Outperforms Demographic Categories

When the researchers clustered individuals by their value profiles rather than demographic categories, something interesting emerged: value-based clusters explained significantly more of the variation in how people rate content. Using value profile embeddings for clustering explained 30-40% more variance in individual ratings compared to demographic-based groupings. The clusters that formed weren’t random—they represented coherent groups of people who shared underlying orientations toward concepts like harm, fairness, authority, and personal freedom.

The team used these value profile embeddings to create what they call “cluster profiles”—aggregate descriptions of groups that share similar values. These cluster profiles could then be used to make predictions for new individuals, even without extensive behavioral history. In the toxicity annotation dataset, value-based clustering produced groups whose members had more consistent rating patterns than groups formed by age, gender, or other demographic variables.

In customer conversations and our early platform tests, we see the same pattern: psychographic and values-based segmentation captures something demographics miss. But until now there wasn’t a systematic, scalable way to extract these value profiles from behavioral data rather than relying on self-reported surveys (which have their own reliability issues). The research suggests that if you can observe enough of someone’s choices, you can infer their value profile—and that profile will generalize to predict their reactions in new contexts.

Finding 3: The Decoder Actually Understands Semantic Differences

This surprised me when I first read through the experiments. The researchers tested whether their decoder model genuinely understood the semantic meaning of value profiles or was just memorizing correlations. They did this by systematically editing value profiles—adding, removing, or negating specific value statements—and observing how predictions changed.

The results held up: when they removed a value statement (like “prioritizes reducing harm”), predictions shifted in the expected direction for relevant content but remained stable for unrelated content. When they negated values, predictions moved in the opposite direction. The model maintained good calibration throughout, meaning when it expressed 80% confidence, it was right about 80% of the time. This suggests the decoder has learned something meaningful about the relationship between stated values and likely preferences, not just surface-level correlations.

For anyone building personalization systems, this is the difference between a system you can audit and explain versus a black box that “just works” (until it doesn’t). When a value-based system makes a prediction, you can inspect the value profile and understand why. When the prediction is wrong, you can identify which value assumption was incorrect. This interpretability isn’t just a nice-to-have—it’s essential for building trust and iterating on your strategy.

Finding 4: Simulating Annotator Populations Reveals Where Disagreement Lives

Perhaps the most practically valuable finding: the researchers showed that value profiles can be used to simulate entire populations of annotators, revealing where genuine disagreement exists versus where apparent disagreement stems from measurement noise. By generating synthetic ratings from diverse value profiles, they could predict which content would produce high disagreement among real human raters.

Imagine being able to preview, before you launch that campaign, how different value-based audience segments will react—not based on demographic stereotypes, but on empirically-grounded value profiles. You could identify content that unifies your audience versus content that will inevitably polarize. You could find the specific value assumptions in your messaging that create friction for otherwise-aligned prospects. Traditional A/B testing tells you which version won on average. Population simulation using value profiles can tell you which version will appeal to which segments—and where you face genuinely contested territory where no single version will satisfy everyone.

The researchers demonstrated this by showing that their simulated annotator populations produced disagreement patterns that matched real-world annotation disagreement with high correlation.

The Navay Connection

This research validates the core premise behind what we’re building: that we can create AI-powered representations of human diversity that are more predictive and more interpretable than traditional demographic segmentation. At Navay, we’re building systems that evaluate content from diverse perspectives—and value profiles represent exactly the kind of principled approach to representing human variation that makes synthetic personas trustworthy.

The information bottleneck architecture creates a human-auditable checkpoint in the prediction pipeline.

The information bottleneck architecture creates a human-auditable checkpoint in the prediction pipeline.

The key insight is the information bottleneck architecture: compress behavioral signals into interpretable language, then use that language to drive predictions. This creates a human-auditable checkpoint in the middle of the pipeline. You can read the value profile. You can ask whether it captures something real. You can identify when it’s wrong. That’s a fundamental improvement over end-to-end black boxes that go directly from behavioral data to predictions with no interpretable intermediate representation.

What This Research Doesn’t Prove

Intellectual honesty requires acknowledging limitations—and there are questions the paper doesn’t answer. This research was conducted on annotation tasks—rating toxicity and social values statements—which may not generalize directly to commercial personalization contexts like purchase decisions or content engagement. The datasets, while substantial, represent specific populations that may not reflect your particular audience.

The value profiles were generated by large language models, which means they inherit whatever biases and limitations those models carry. The researchers acknowledge that value profiles are “necessarily imperfect compressions” and that some predictive information is lost in the compression process. The 71.1% information retention figure is impressive, but it also means roughly 30% of the signal is gone.

Finally, this is observational research on existing datasets. The researchers didn’t run controlled experiments showing that marketing campaigns personalized using value profiles outperform demographic targeting. That’s the next research frontier—and the practical validation that will determine whether this approach delivers business value. Whether the gains hold in the messy reality of commercial marketing remains an open question, and anyone who claims certainty is selling something.

What I’m Watching

Here’s the strategic question worth asking: if value profiles work, why isn’t everyone already doing this? Part of the answer is that the infrastructure didn’t exist until recently—you need capable LLMs to generate and decode the profiles. But part of it is that the marketing industry has decades of momentum behind demographic targeting, and switching costs are real.

The economics suggest this shift may happen faster than most expect. If you can predict individual preferences 30-40% better using value profiles than demographics, and if you can explain your predictions in readable English, the compound advantage over time is enormous. Every personalization decision gets slightly better. Every feedback loop closes faster. The interpretability alone is worth the transition cost, because you can finally debug why your personalization isn’t working instead of just throwing more data at the problem.

The research is clear on which approach predicts preferences better. The question is whether the industry will catch up to the research, or whether the companies that adopt value-based personalization early will quietly compound their advantage while everyone else optimizes their demographic segments.

Demographics tell you who someone appears to be. Value profiles tell you what they actually care about. I know which one I’d rather build on.

This analysis is part of Navay’s ongoing coverage of research advancing the science of human variation modeling. We translate academic findings into practical insights for marketing professionals who want to understand how AI can better represent the diversity of human perspectives.