Focus Group Bias Is Worse Than You Think: What 70 Years of Research Confirms

Every marketer knows focus groups can be messy. But most underestimate how systematically the mess skews results. Decades of research—from Solomon Asch’s landmark conformity experiments in the 1950s to replications published just last year—paint a consistent picture: when people give feedback in groups, social dynamics warp what they say in predictable, measurable ways. And those distortions don’t cancel out. They compound.

If you’re making creative decisions based on focus group feedback, you’re building on a foundation that the research says is structurally biased. Here’s what the science actually shows.

TL;DR

- 33% of responses conform to group consensus rather than reflecting actual individual opinion — a rate that’s barely changed since 1951

- Financial incentives reduce but don’t fix it — paying for accuracy only drops conformity to 25%

- Subjective questions make it worse — conformity climbs to 38% for opinion-based questions, exactly where creative feedback lives

- 76% of participants conformed at least once — three out of four people override their own judgment to match the group

This isn’t a rounding error or a quirk of bad moderation. It’s a deeply studied phenomenon that persists across decades of replication. When you collect feedback in a group setting, you’re measuring social dynamics as much as genuine reactions to your creative work.

Data from Franzen & Mader (2023), PLoS One. CC BY 4.0.

Data from Franzen & Mader (2023), PLoS One. CC BY 4.0.

The Research

The findings below draw on five peer-reviewed studies spanning three decades. The primary anchor is a 2023 large-scale replication of the Asch conformity experiment, supported by systematic reviews and focused studies on social desirability, group dynamics, and individual versus group feedback.

Primary Paper: “The Power of Social Influence: A Replication and Extension of the Asch Experiment” Authors: Axel Franzen and Sebastian Mader Published: 2023, PLoS One, Vol 18, Issue 11

What They Tested

Franzen and Mader wanted to know whether Asch’s original conformity findings—first published in 1951—still hold up. The original experiment was elegantly simple: show people lines of obviously different lengths, plant confederates who give the wrong answer, and measure how often participants go along with the group despite seeing the correct answer with their own eyes. Does social pressure still override individual judgment seventy years later?

They also extended the experiment in two directions that matter for marketers: What happens when you add financial incentives for accuracy? And what happens when the question shifts from objective facts to subjective opinions—like political views?

How They Tested It

The researchers recruited 202 participants for an in-person experiment with trained confederates who unanimously gave incorrect answers on 12 of 18 line-comparison trials. A control group of 58 participants completed the same task without confederates. Additional conditions introduced monetary rewards for correct answers and tested conformity on political opinion questions.

What the Focus Group Research Reveals

Finding 1: One-Third of All Responses Conform to the Wrong Answer

In the 2023 replication, 33% of responses conformed to the clearly incorrect group consensus—closely matching Asch’s original finding of 36.8%. Even more striking: 76% of participants conformed at least once during the experiment. That’s three out of four people overriding their own perception to match the group, at least some of the time.

The researchers found that conformity wasn’t random noise. It was systematic and predictable. For marketers, this means focus group feedback doesn’t just have variance—it has directional bias. Early opinions anchor later ones, and minority viewpoints get suppressed even when they’re correct.

Finding 2: Money Helps, But Doesn’t Fix It

When participants were paid for correct answers, conformity dropped from 33% to 25%. That’s a meaningful reduction, but a 25% error rate is still enormous. One in four responses remained distorted by social pressure even when participants had a direct financial incentive to ignore the group and trust their own eyes.

This finding undercuts a common assumption in market research: that motivated respondents give you better data. They do, marginally. But the social pressure operates at a level that financial incentives can’t fully reach. As Bispo Junior’s 2022 systematic review in Revista de Saude Publica documents, social desirability bias works through two mechanisms—self-deception (unintentional distortion) and impression management (deliberate distortion)—and the unintentional component is resistant to incentive structures because participants don’t realize they’re doing it.

Finding 3: Subjective Questions Make It Worse

When Franzen and Mader shifted from objective line comparisons to political opinion questions, conformity climbed to 38%. This is the finding that should alarm marketers most. Creative evaluation is inherently subjective—there’s no objectively “correct” reaction to an ad, a landing page, or a brand concept. And the research shows that subjectivity amplifies conformity rather than dampening it.

Bergen and Labonte’s 2020 study in Qualitative Health Research adds crucial texture here. They found that focus group participants consistently depict reality in what the researchers call “socially acceptable” ways. When one participant held higher social status than others, the effect intensified—lower-status participants conformed to the higher-status person’s opinions. In a typical focus group, where you might have a mix of confident and reserved personalities, the loudest voice doesn’t just get heard first. It reshapes what everyone else says.

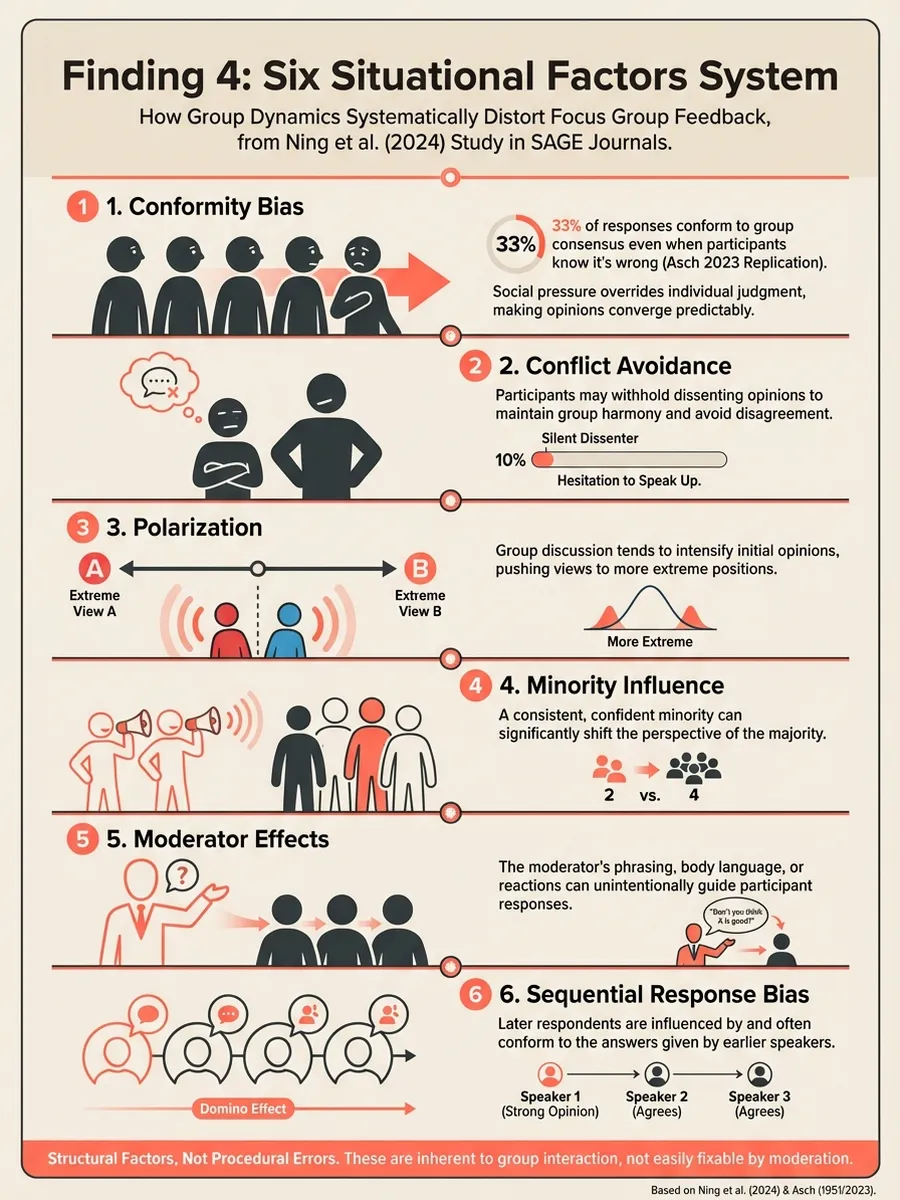

Finding 4: Six Situational Factors Systematically Distort Group Feedback

Ning et al.’s 2024 study in SAGE Journals identified six situational factors that affect focus group reliability: conformity, conflict avoidance, polarization, minority influence, moderator effects, and sequential response bias. That last one is particularly insidious—later respondents systematically conform to the answers given by earlier respondents. The order in which people speak literally changes the data you collect.

This isn’t a moderation problem you can train your way out of. These are structural features of group interaction that persist regardless of the moderator’s skill. The researchers’ framing is instructive: these aren’t “problems to fix” but rather “situational factors” inherent to the methodology itself.

Finding 5: Individual Feedback Outperforms Group Feedback

Archer-Kath, Johnson, and Johnson’s 1994 study in The Journal of Social Psychology compared individual feedback against group feedback and found that individual feedback was significantly more effective for achievement motivation, actual achievement, and positive relationships. Participants who received individual feedback rather than group feedback produced better outcomes across every measured dimension.

For creative testing, the implication is direct: if you want honest, differentiated reactions to your work, you need to collect them individually. Group settings don’t just add noise—they actively degrade the quality of the signal.

What This Means for Your Creative Testing Process

The research points to a structural problem, not a procedural one. You can’t moderate your way out of conformity bias any more than you can wish away gravity. The physics of group interaction bend feedback toward consensus, suppress dissent, and amplify whoever speaks first or loudest.

This is part of why we built Chorus the way we did. Each Virtual Voice in a Chorus Creative Check responds independently—no participant can hear, influence, or conform to another’s reaction. There’s no sequential response bias because there’s no sequence. There’s no social status hierarchy because there’s no social interaction. The Asch experiment can’t replicate in a system where nobody can see what anyone else said.

It’s a bit like the difference between polling people in a town square versus giving each person a private ballot. Researchers have understood this distinction for decades—the secret ballot exists precisely because public voting is subject to social pressure. In Isaac Asimov’s Foundation, Hari Seldon could predict the behavior of populations but not individuals, because individual choices are too easily swayed by immediate social context. Focus groups hand you population-level noise and call it individual insight. The research says: collect individual reactions first, then look for patterns. Not the other way around.

The Caveats

These studies have real limitations worth noting. Asch-style experiments use objective perceptual tasks (line length comparison), and while the 2023 replication extended to political opinions, creative evaluation has its own dynamics that aren’t perfectly captured by either paradigm. The 33% conformity rate is a useful benchmark, not a precise prediction for every focus group setting.

The individual-versus-group feedback study (Archer-Kath et al., 1994) examined cooperative learning contexts, not market research specifically. The principle translates—individual feedback structures outperform group ones—but the magnitude of the effect may differ in commercial research settings. Bergen and Labonte’s work and Bispo Junior’s systematic review focus on qualitative health research, where social desirability around health behaviors may be stronger than in commercial contexts, though the underlying mechanisms (impression management, self-deception) are domain-general.

More research specifically comparing AI-generated individual feedback against traditional focus groups would strengthen the case. The theoretical alignment is strong, but direct head-to-head comparisons are still emerging.

Read the Full Papers

-

Franzen, A., & Mader, S. (2023). The Power of Social Influence: A Replication and Extension of the Asch Experiment. PLoS One, 18(11). DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0294325

-

Bergen, N., & Labonte, R. (2020). “Everything Is Perfect, and We Have No Problems”: Detecting and Limiting Social Desirability Bias in Qualitative Research. Qualitative Health Research, 30(5). DOI: 10.1177/1049732319889354

-

Bispo Junior, J. P. (2022). Social Desirability Bias in Qualitative Health Research. Revista de Saude Publica, 56:101. DOI: 10.11606/s1518-8787.2022056004164

-

Archer-Kath, J., Johnson, D. W., & Johnson, R. T. (1994). Individual Versus Group Feedback in Cooperative Groups. The Journal of Social Psychology, 134(5). DOI: 10.1080/00224545.1994.9922999

-

Ning, X., Liu, Y., Miao, J. L., & Li, W. L. (2024). Enhancing the Potentials of the Focus Group Discussion. SAGE Journals. DOI: 10.1177/16094069241306332

This post is part of our Research Radar series, where we translate academic findings into practical insights for marketers.